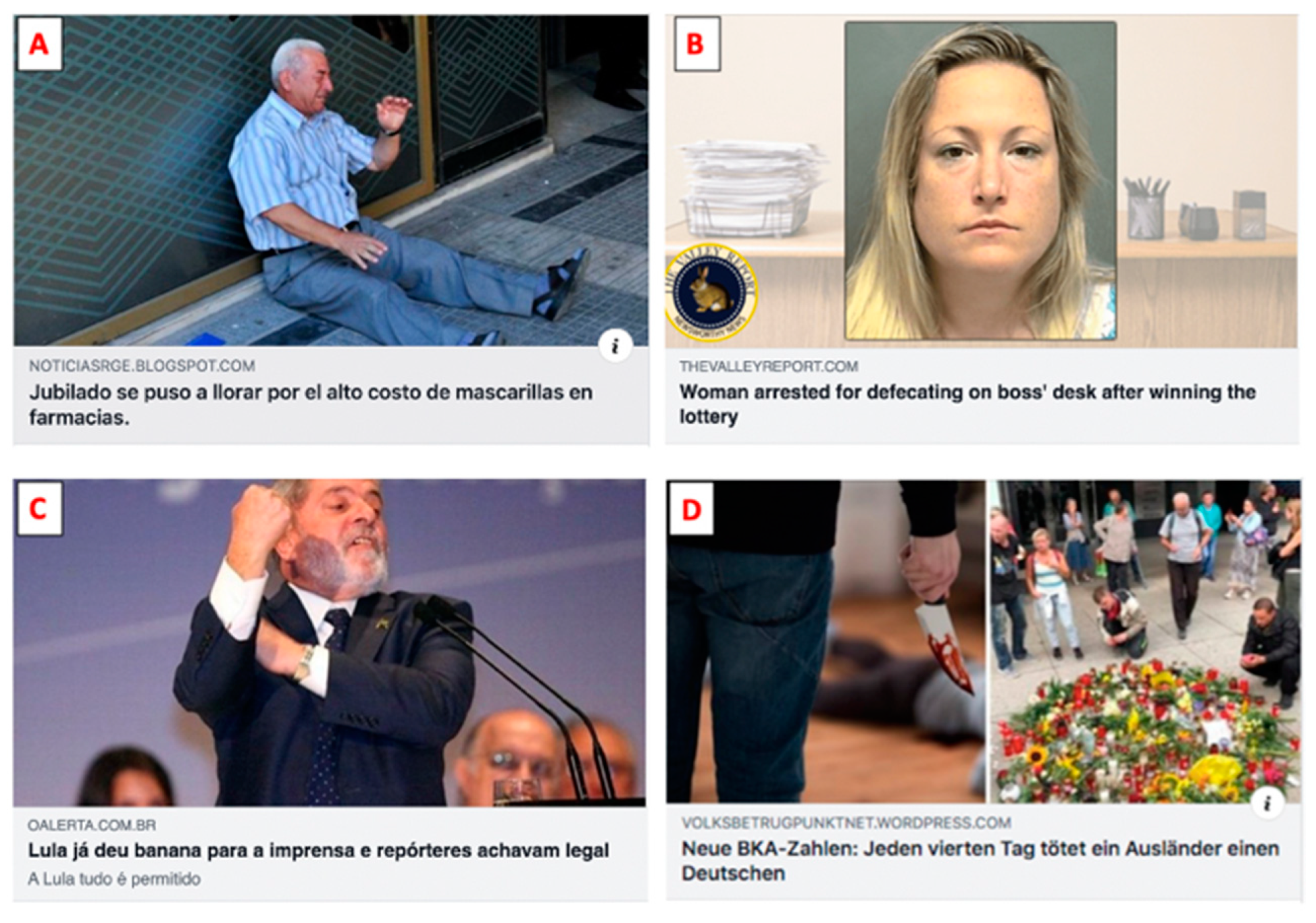

Facts About Examples of Fake News - Fact Check: How to decipher online Revealed

from web site

Fake News: Recommendations - Media Literacy Clearinghouse - Questions

Although seemingly avoiding "any type of censorship, either public or personal," it promotes greater self-regulation in the brief term, with a long-range goal of establishing a Code of Practices to motivate openness, media literacy, variety, the advancement of tools to "tackle" disinformation, and more research study to monitor and assess the sources and effect of fake news.

Its Dutch challengers define it as a state publication that "passes judgments whether a publication in the complimentary media consists of the right views or not. If your publication ends up in its database, you're officially labeled by the EU as a publisher or disinformation and phony news." These examples show how problematic it can be when governmental entities end up being arbiters of what holds true and what is phony.

Supreme Court choice, New York Times v. Sullivan. Constitutionalizing the Right to Be Incorrect The Sullivan case arose during the civil liberties motion, involving a Montgomery, Alabama, public safety commissioner named L.B. Sullivan, who took legal action against the New York Times after it published a fundraising advertorial that described law enforcement actions designed to prevent demonstrations by activists such as Martin Luther King Jr.

10 Easy Facts About Working to Stop Misinformation and False News - Facebook Described

Sullivan claimed that the ad, that made several factually inaccurate claims about the Montgomery cops, had actually defamed him personally, despite the fact that he was not identified by name or title. In other words, Sullivan claimed the publication was fake news. He sought and won $500,000 in damages, without being required under Alabama law to show that his track record was in fact damaged.

This regard to art is specified as understanding that the declaration was incorrect, or evidence that the publisher acted with reckless disregard for the truth. A showing of hatred or ill will, referred to as common law malice, is not sufficient to fulfill that test. According to This Piece Covers It Well , because some factual errors are inevitable even in the most cautious news reporting, this security is necessary to avoid media self-censorship, to promote energetic reporting on federal government and public authorities, and to preserve our "profound nationwide dedication to the concept that debate on public problems ought to be uninhibited, robust and wide-open." In subsequent years, the First Change defense broadened to include suits by public figures as well as government authorities.